Second Sons, Sweet Lands, and the Mystery of “Du-Gay” Art

In 1966, I dated a French-speaking sugar engineering student at LSU surnamed Chasteau de Balyon. His family had run sugar plantations for generations on the island of Mauritius—first under the French, then the British. He was handsome, bright, and utterly sure of his place in a long and exotic colonial tradition. I didn’t realize it at the time, but he was part of a pattern I’d recognize again and again in my later research:

Younger sons of elite French families sent out to tropical lands—Louisiana, Haiti, Guadeloupe, Mauritius—to make their fortunes in sugar.

Here in Louisiana, the Dugué de Livaudais family exemplified that same story. French Catholic aristocracy, they settled in the territory long before the Louisiana Purchase and built a sugar empire on the west bank of the Mississippi River—in Lafourche, St. James, and Iberville Parishes. Their holdings were so extensive that their hub became known as Vacherie Dugué Livaudais—the origin of today’s town of Vacherie, Louisiana.

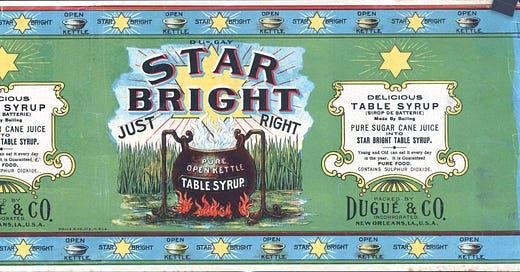

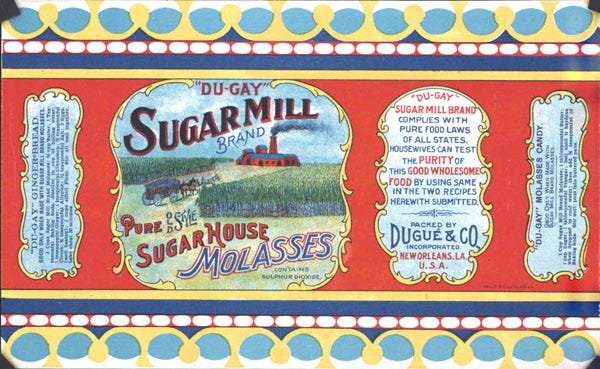

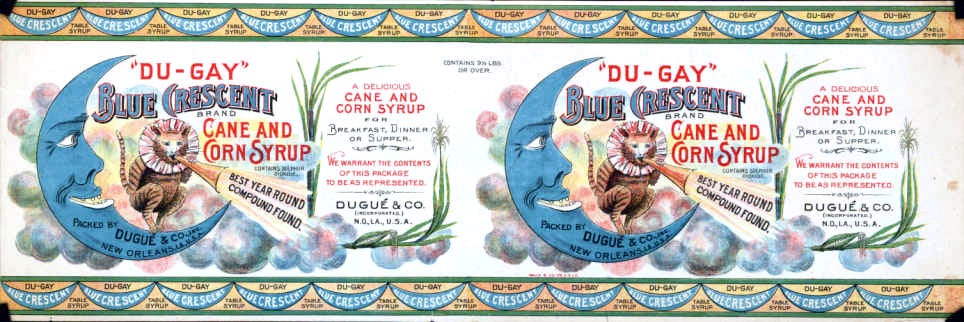

But what makes them especially dear to me is their witty, theatrical branding from the late 1800s, when they pivoted from sugar planting to syrup packaging in New Orleans. Through Dugué & Co., they marketed labels like these from the Fabled Labels Archive:

The labels are utterly charming—loose, whimsical, and distinctly French in spirit. They’re a world apart from the highly structured, jewel-tone work of Frederick Susus von Ehren, the master chromolithographer behind most of the Walle Corp labels in my collection.

These Dugué labels are not his.

They’re full of movement, sly humor, even poetry. The Star Bright label, for instance, depicts a bubbling cauldron over a roaring fire—bold, unpolished, practically vibrating. It’s not just syrup—it’s alchemy.

I wish I knew who drew them.

There are no artist signatures. No studio marks. Just a trail of trademarks and dissolutions, lawsuits and newspaper ads, before the company disappears around 1898.

But the labels endure. And now they live again—on mugs, prints, and in this archive. Even the name got its moment of brilliance: “Du-Gay”, a phonetic rebrand to help Americans pronounce Dugué. Très intelligent.

Maybe some descendant out there still knows who held the stylus.

Until then, I’ll keep preserving these fragments—one label at a time.

—Sharon

Fabled Labels